In the last few months, since the start of the war on Gaza, activists across the motu have engaged in protest, after protest, after protest. Most of these public displays of solidarity with the Palestinian people have been peaceful with an uneventful Police presence using protest actions that are non-arrestable and protected by law.

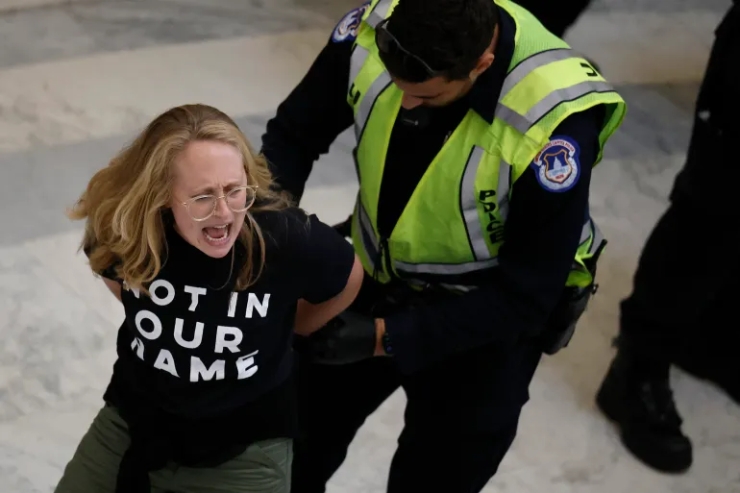

However, on a few occasions, activists have shifted tactics to civil disobedience by disrupting meetings, occupying public spaces, interrupting traffic flow, or damaging property. When this happens, Police tactics alter. Police have deployed physical force, used pepper spray, made arrests and pressed criminal charges.

Justice for Palestine has not participated in direct action tactics to date. We recognise direct action as a legitimate protest tactic but recognise the risks of stepping outside the boundaries of institutional protest actions–like marches, rallies, and political advocacy–that are protected by law. Like other human rights NGOs, Justice for Palestine does not rule out using direct action tactics–such as blockades and occupations–in a planned, deliberate, disciplined, and nonviolent way. We reserve the right to choose to use extra-institutional protest methods, like NVDA, where escalating the action is proportionate to the harm caused by the targets–such as arms dealers involved in supplying the Israeli military or cargo ships transporting arms to Israel–and where this connection would be easy for the public to apprehend.

All activists must be fully aware of the implications of different approaches to direct action, the difference between violent and nonviolent direct action, and what makes for safe and effective direct action. In addition, as an organisation with headquarters in Pōneke, we choose to operate under Te Kahu o Te Raukura, the cloak of aroha and peace.

In what follows, we explore the implications of Te Kahu o Te Raukura, discuss the law regarding protests, explain the use of civil resistance that goes beyond the law, consider the implications of the Police use of force, and identify issues for activists to consider when engaging in planned and deliberate NVDA.

Te Kahu o Te Raukura

Achieving justice and peace in Palestine is the central kaupapa of Justice for Palestine. We are also mindful of our position as activists on the land of Aotearoa and of our obligation to honour te Tiriti. In Pōneke, honouring te Tiriti means working closely with Taranaki Whānui as mana whenua, affirming their mana and rangatiratanga. In particular, in our actions, we seek to uphold Te Kahu o Te Raukura, the cloak of aroha and peace.

This is a Parihaka tikanga. Te Raukura–three feathers representing honour, peace, and goodwill–were used by followers of Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi at the settlement of Parihaka in Taranaki where nonviolent action was practised to assert their rangatiratanga, their right to whenua and to resist an invasion of the settlement by 1,600 armed Pākehā Police.

During the armed Police invasion on 5th November 1881, the Parihaka nonviolent resistance movement was met with the arrest and imprisonment of leaders, physical and sexual assault of the Māori inhabitants, the destruction of the settlement and the confiscation of land. But the lesson of Parihaka is not the historical stain of Pākehā violence, it is the dignified stance of Te Whiti, Tohu and their followers, the protection of the Parihaka people–who would otherwise have been slaughtered–and the inspiration provided by their example to many others resisting oppression and colonisation throughout the world, including Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

“Though the lions rage, still I am for peace…Though I be killed, I yet shall live; though dead, I shall live in peace which will be the accomplishment of my aim.”

Te Whiti o Rongomai.” (5 November 1881)

Justice for Palestine respects Te Kahu o Te Raukura and its commitment to honour, peace, and goodwill in our actions.

What the law says

It is important to note that we all have a legal right to peaceful protest, as written in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act (1990). We have

- the right to meet and organise with others – “Freedom of association”

- the right to gather and protest with others – “Freedom of peaceful assembly”

- the right to speak out and say what you think – “Freedom of expression”.

But there are limitations on those rights, and some activists may–intentionally or unintentionally–take actions that Police can interpret as breaking the law. As the Community Law Centre Manual states:

“So long as you’re not breaking the law, government organisations and the police should recognise and protect your right to protest.”

Community Law Centre

We strongly recommend that all activists involved in public demonstrations, even lower-risk actions like joining marches and rallies, become aware of their duties and rights under the laws relating to protest and activism. The Community Law Centre Manual has a whole chapter dedicated to Activism: Your Rights to Protest and Organise for Change. If you do nothing else, please read this and circulate it to your friends and fellow activists before going to the next rally or march.

This is essential reading. Armed with this knowledge, you will be able to make better sense of police actions and be more confident in challenging them when appropriate. This reading will also inform you of what is likely to happen if you decide to practise civil resistance and deliberately break the law.

Civil resistance

Throughout history, oppressed peoples have maintained the right to civil disobedience, or civil resistance, as a positive force for social change. International examples include the US civil rights movement and Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the UK.

In Aotearoa, we have a rich history of civil resistance from the Parihaka movement to the Bastion Point occupation and more recent protests against the Wellington Arms Fair.

Outside of situations of oppressive, military occupation, very few activists advocate violence as a way to achieve social change. Even in the occupied Palestinian territories, armed resistance is the exception rather than the rule and the principles of the BDS movement are explicitly nonviolent.

For Justice for Palestine, advocating nonviolent action is not an absolute moral stance. It does not reflect a view on the right of oppressed peoples to choose their own methods of resistance. In particular, when a territory is under military occupation, as the Occupied Palestinian Territories have been since 1967, the UN recognises “the legitimacy of the struggle of peoples for independence, territorial integrity, national unity and liberation from colonial and foreign domination and foreign occupation by all available means, including armed struggle”.

However, in the context of the international Palestinian solidarity movement, the predominant forms of protest are nonviolent, including legal forms such as marches, rallies, vigils, petitions, political lobbying, and some forms of nonviolent direct action such as blockades, sit-ins, boycotts, and strikes.

There is extensive academic literature on the efficacy of violent versus nonviolent movements and a very mixed range of findings, much of which depends on the unique social and political contexts of the struggles examined. However, many scholars and activists, such as Erica Chenoweth and Judith Butler, advocate for nonviolent civil resistance. Erica Chenoweth argues that nonviolent civil resistance is more effective because it:

- Enables broader and more diverse participation in movements for social change

- Is more likely to inspire defection from the ranks of the opposition including political elites and security forces

- Has a much broader and richer set of tactics to draw upon

- Is more effective at maintaining movement discipline even when oppression escalates.

This is obvious to most activists, and we doubt that anyone in the Palestinian solidarity movement in Aotearoa would deliberately set out on a planned campaign of violent direct action. However, on some occasions, protesters in Aotearoa have found themselves on the wrong side of the Police use of force. What has gone wrong?

Police use of force

There are many valid critiques of Police and policing in Aotearoa. That is not surprising. Police in Aotearoa, and all jurisdictions, have access to arms and are legally authorised by the state to use force that can range from so-called “empty hand techniques” to the use of OC spray (pepper spray), batons, tasers, sponge bullets and deadly force. New Zealand Police published an overview of their use of force, including the statement that “the use of force is governed by statute, and any force used must be necessary, proportionate and reasonable.”

However, the experience of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US and the over-representation of Māori in the justice system here in Aotearoa make us wary about how “necessary, proportionate and reasonable” use of force might be when Police are policing protests that include Māori, people of colour and other systematically oppressed social groups.

There are many progressive arguments for the abolition of prisons, Police and other oppressive social institutions. This is not the place to discuss these arguments. In this article, we only want to explore the implications of existing Police powers for protest actions and how we can attempt to keep people safe when using NVDA tactics.

When deciding how to police operational situations, including public protests, New Zealand Police refer to their Tactical Options Framework, an “operational guidance tool that assists constables to appropriately decide when, how, and at what level to use a tactical option”. These “tactical options” are presented as a continuum of force from simple police presence to the use of lethal force. Lethal force is unheard of at a public protest in Aotearoa but the use of force–from empty hand techniques through pepper spray to sponge bullets–has been deployed. What triggers the use of Police force? And how can we manage more assertive protest actions in ways that keep people safe and respect Te Raukura of honour, peace, and goodwill?

The Police Tactical Options Framework maps the degree of force proportionate to the behaviour of people at an incident, including protest actions, and the perceived degree of threat.

The Tactical Options Framework describes a continuum of behaviours from being cooperative to passive resistance, to active resistance, to assault and–at the most extreme end of the spectrum–causing grievous bodily harm or death. The response of Police should be proportionate to the perceived threat.

The most significant aspect of the framework for protest actions, especially civil resistance and nonviolent direct action, is the perceived distinction between passive and active resistance. During most rallies and marches, where our rights to peaceful assembly are protected, the main concern for Police is health and safety and to ensure public order. They use their presence and “tactical communication” to shepherd marches and ensure safety. When a protest is self-disciplined and well-marshalled by trained activists Police tend to have a very low profile.

However, when an action is focused on civil disobedience and involves activity such as actively blockading a road or access to an event, disruptively occupying a public space, daubing a building with paint or graffiti, illegal entry to premises, property damage, or any other arrestable action, then Police tactics are likely to change. Some use of force and the arrest of participants should be anticipated.

In the remainder of the article, we have drawn on a range of activist literature (with some sources at the end) to identify issues that activists should consider before embarking on NVDA. Attention to these factors will help to ensure that actions are well-planned, deliberate, and as safe and effective as possible.

However, please note that there are no guarantees. The outcomes of NVDA can be highly unpredictable, and the most passive forms of resistance can still encounter Police violence.

NVDA issues to consider

- Ensure the use of NVDA is deliberate, well-planned and expected by all involved in an action. Anyone can practise NVDA and sometimes elements of NVDA can arise spontaneously as a response to counter-protesters, or an unexpected change in Police tactics, or as a result of actions by individuals or small groups at a march or rally. However, spontaneous, unplanned NVDA actions, or NVDA actions that emerge during standard less-arrestable marches and rallies, present risks to people participating in protests. This includes children and vulnerable people who have not given consent and may not choose to take part in NVDA or experience its consequences. Planned action ensures risks can be managed, that people volunteer for NVDA in full knowledge of the possible consequences and that the action taken is as safe as possible.

- Train activists in planning and leading disciplined NVDA. NVDA often goes beyond legal, less-arrestable forms of action in ways that can be interpreted by Police as breaking the law. This will always present Police with a concern and they may choose to use force to break up the action and arrest at least some activists. Over the years, activists have developed techniques and skills to ensure that NVDA actions are forceful, effective and nonviolent while being as safe and effective as possible. For example, a blockade is more effective when activists sit with arms locked together. Some techniques make it much more difficult for Police to use “empty hand techniques” to push activists out of the way. If the resistance remains passive–without pushing back or shouting at Police–the rationale for a decision to use other tactics, such as pepper spray, becomes harder to make. This doesn’t mean Police won’t choose to escalate the use of force, just that it is harder to justify especially if the response remains passive. Police decisions to use force in these circumstances can backfire regarding how events are reported in the press or decided upon in a court of law. There are other practical issues to consider when engaging in planned and deliberate NVDA. For example, if activists are standing holding flags or placards during NVDA actions, they can become involved in physical struggles with Police attempting to remove these items from their grip. These struggles can be interpreted as active resistance–perhaps even assault–and lead to the escalation of Police use of force. The resources at the end of this article describe many skills and techniques, based on years of activist experience, that strengthen successful NVDA. Activist education makes planned, deliberate and effective NVDA possible.

- Agree on the limits of each instance of NVDA and your expectations of activists. For example, some activists decide not to verbally abuse Police or members of the public, even when taunted, because this behaviour raises the temperature and may increase the risk of Police escalating the use of force, or the risk of physical assault by angry members of the public. Other examples of NVDA discipline concern planned and deliberate decisions about acts of intentional damage to property or illegal entry to premises. Intention to commit such acts raises the risk of arrest and prosecution. Some activist groups deliberately exclude such acts and signal this to activists and Police. See, for example, page 55 of the NVDA Training Guide by the Direct Action Movement in Australia who give Police a copy of a ‘nonviolent discipline’ leaflet at the beginning of their action. Other groups accept property damage and illegal entry to premises as acceptable parts of the action, especially when the target is an arms dealer. NVDA tactics should be proportionate to the harms associated with the target and consider the public perception of such acts.

- Make plans to include activists with different roles in the action. Activists can adopt several possible roles during NVDA to ensure it is safe and effective. Different activist groups have different views on the necessity of these roles, and what is required may differ for different actions. Some NVDA groups include a Police liaison person. The Police liaison would not participate in the action but be on hand to communicate with Police and be the spokesperson for the action. The principal aim of the Police liaison is to reduce the chance that Police use of force is escalated. Some NVDA groups may include legal observers. Legal observers do not participate in the action but observe and film it as appropriate. If they know the names and contact details of participants, they can inform their contact person should they be arrested or harmed during an action. Many NVDA actions will include first aiders. Like the Police liaison and legal observers, these people would not participate in the action but be on hand with a basic first-aid kit to help with immediate injuries including incidents of pepper spraying. Many other roles can be included in planned and deliberate NVDA (see pages 54-60 of the DAM NVDA Guide).

Justice for Palestine considers NVDA an acceptable tactic to support the movement for Palestinian rights. In our view, it should be led by activists trained in NVDA techniques. It should also be proportional, planned and deliberate with carefully selected targets to reduce the risk of harm and unintended consequences. However, it is important to note that, no matter how proportional, planned, and deliberate NVDA is, Police violence, arrest and criminal charges are always a risk. NVDA activists must be fully aware of these risks and of the consequences for their wellbeing.

Resources on NVDA

NVDA guide & training: The Direct Action Movement

Beautiful Trouble: Creative tools for a more just world

Toolkit for nonviolent direct action

International Centre on Nonviolent Conflict

Martin Luther King’s philosophy of nonviolence

TED talk: The success of nonviolent civil resistance: Erica Chenoweth at TEDxBoulder

“Non-violent resistance works.” A Talk Europe! interview with Judith Butler

The path of most resistance: A step-by-step guide to planning nonviolent campaigns

Global nonviolent action database

Making or breaking nonviolent discipline in civil resistance movements

You must be logged in to post a comment.